A few days into my Yellowstone adventure I experienced a wonderland overload. By day seven, the Old Faithfull clockwork eruptions no longer made me gasp with amazement — the chronic burps of the geyser became an anticipated routine. The Grand Canyon of Yellowstone was incessantly picture-perfect, but because I lack an artistic ability I couldn’t paint a masterpiece — I could only ogle over the colorful rock formations and gape at the Yellowstone River as it carved the canyon below us. How long can one stand around and stare? The guide book to Yellowstone recommended longer and more challenging hikes, but these were inappropriate exploits for me and my old-faithful father. Having witnessed most of the natural wonders in the park, we were ready to venture out to explore the areas beyond the East Entrance.

Cody is located a little over two hours from the Canyon campground where as a temporary amusement we lived out of our RV. The town was established in 1896 by the famous Buffalo Bill Cody, an American Civil War soldier, bison hunter, and a showman. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows depicting cowboys and Indians exposed the world to the American frontier. Driving into the city on Highway 14 we noticed a large exhibition arena. In the showman’s tradition the town of Cody offers a daily Stampede, one of the longest running rodeos in America. We stopped to inquire about the tickets, but the Stampede started at 7:00 PM and neither my dad nor I was eager to drive back to Yellowstone after dark — negotiating through windy canyons and vast prairies. The Stampede was off our agenda but the Old Trail Town Museum just a few yards down the road was on. We parked the car and entered an open-air museum comprised of antique frontier buildings — disassembled, transported, and faithfully reassembled on the exact site chosen by Buffalo Bill for the original City of Cody.

The Old Trail Town is hardly a “town” but merely a long strip of prairie dirt lined on both sides with buildings. The center of the strip hosts a collection of decrepit wagons, beaten-down by the weather the wagons are slowly losing their battle with time – occasionally a tumble weed blows through.

My perception of the wild-west aligns with what Buffalo Bill presented to his audience — his vision fueled the story lines of Hollywood Westerns projected to the world. In the seventies Bonanza aired in Poland — new episodes ran every Saturday evening. With regularity prescribed by the TV Guide – I sat with my family in front of our black-and-white TV and watched the Saga of the Ponderosa. Bonanza instilled in me an image of the wild-west – the image, complemented by the tough characters played by John Wayne in numerous Western movies.

I envisioned tobacco-chewing cowboys with gun-belts, bucket hats, and spurs attached to their dusty boots — and peace-pipe smoking Indians with feathers in their hair, painted faces, wearing leather tunics elaborately adorned with beads. Living across the ocean, I was neither vested into American culture nor knew much about the U.S. history; consequently, my mind did not categorize either group as good or bad — both were equally exotic to a Polish kid.

What I did judge, with a warranted disapproval, were the outlaws who robed trains and banks, frequented brothels and saloons, and ended their lives in the middle of a dirt street just like the one in Old Trail Town. I recalled a mano-A-mano shoot-out scenes with the town’s folk watching and the undertakers measuring one or both men for a premade six-sided, hexagonal coffin (extra credit: google the difference between a coffin and a casket).

Walking around the open-air-museum, I hoped to put aside Hollywood imagery and get a more accurate knowledge of what life in frontier America was like?

The Old Trail Town offered examples of various man-made structures — my dad and I walked through trapper, scout, and frontier cabins, a schoolhouse, general store, commissary, saloon, Bonanza post office, blacksmith shop, and a wagon barn. We looked at furniture, clothes, tools, items of general use, and rustic decorations which were mostly animal antlers and taxidermy pieces. And while we were looking at genuine artifacts, I could not see, feel, nor imagine the “real-life” of a wild-west town — this was merely a collection of carefully preserved buildings – living history was not jumping out at me.

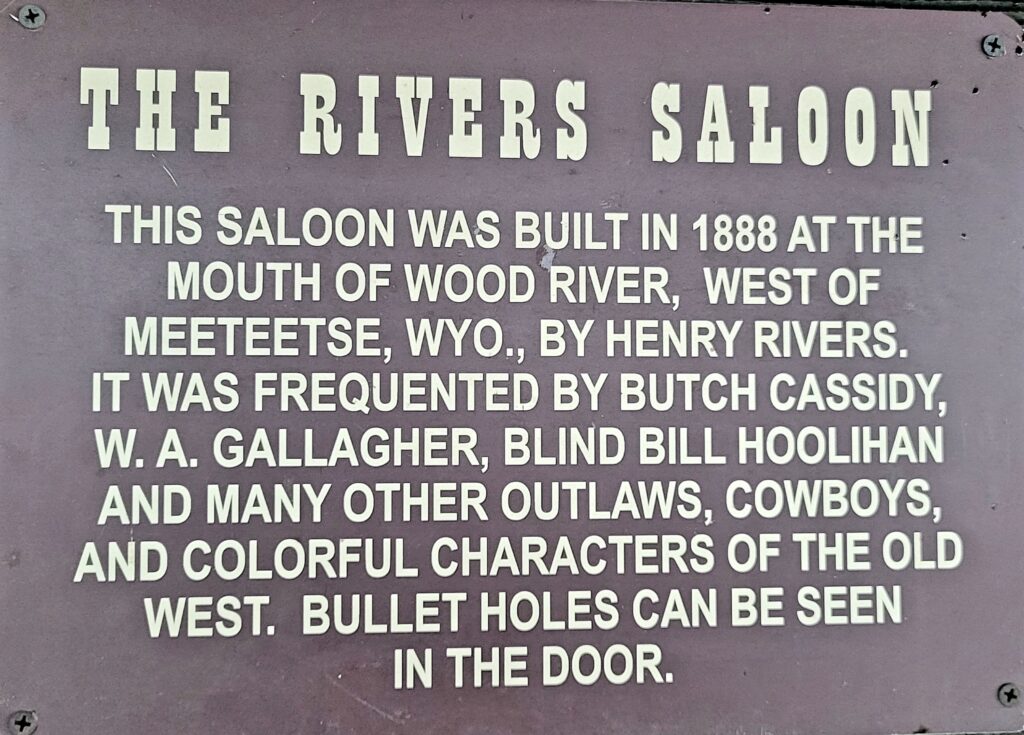

In front of the Rivers Saloon, I read a posted sign: The Rivers Saloon … It was frequented by cowboys, goldminers, outlaws, and other colorful characters of the Old West. Bullet holes can still be seen in the door.

Bullet Holes — I walked inside. The place was clean and felt cozy with walls covered with merlot-red fabric tapestries – I looked around and thought, this saloon is too clean, too small and it doesn’t even reek of whiskey. With interest, I appreciated the authentic oil lamps scattered around the room, but the bright shine of an electricity chandelier hanging from the celling disturbed the ambiance – it was not very 1888’s. Pretending like I belonged, I leaned on the bar that separated the proprietor from his clients. Another counter just beyond was lined with whisky bottles and shot glasses – at the center was an old-timey cash machine adorned in elaborate gold decorations. I looked up and a reflection of a modern woman starred back at me from a mirror on the back wall — she did not belong in this picture. Wait — that’s me, never mind. I looked to the left where stood a debilitated up-right piano – this one for sure can no longer be tuned. Back towards the door was a single round table with four wooden chairs scattered around and a few playing cards carelessly left on its surface as if Butch Cassidy and his gang left the saloon in haste.

I always imagined that Western saloons had no less than five tables, enough for the rowdy clients to pick a fight, throw some chairs, break a few whisky bottles on each other’s heads — then shoot out the mirror behind the bar. The real Rivers Saloon seemed too small to host a good old bar brawl. Another missing feature was a double action swinging door through which a half-crazed outlaw could enter to rob a drunk, albeit recently up on his luck prospector. The prospector’s new best-friends, in appreciation for unlimited whiskey shots, would throw the outlaw out onto the street where John Wayne, the fastest gun in the west, would shoot him hence completing a scene from just-another-day in the wild-west frontier town.

Examining the bullet holes, I wondered, were the nineteenth century frontier towns rowdy, dangerous, and packed with colorful characters? Some historians say that these towns were not full of mischief, mayhem and murder as depicted in Hollywood movies. The open-air-museum, clean and impeccably organized with informational tablets posted in front of every structure provided a setting but failed to deliver the spirit of the days long gone.

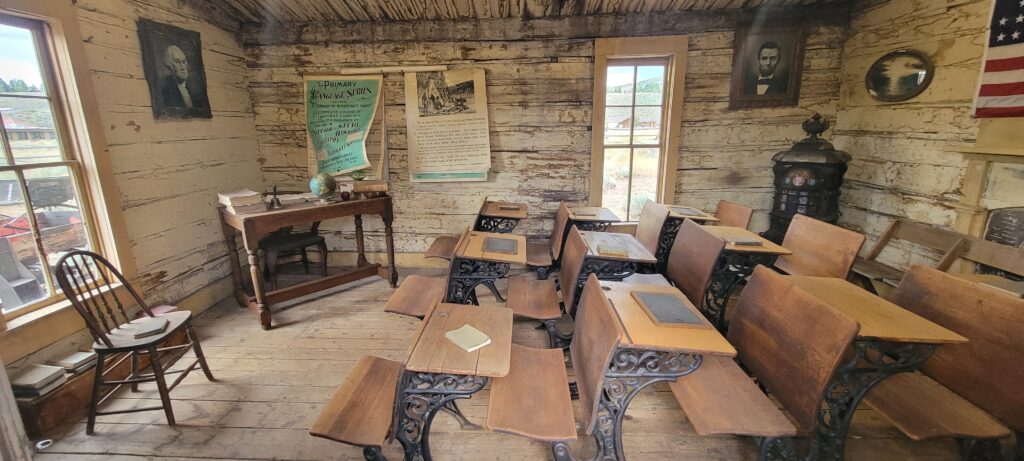

I stepped into the next building which was a frontier school. Coffin School (1884) was a very different space from the saloon next door and with its orderly positioned student desks could easily serve as a set for the Little House on the Prairie. As I strolled between the desks, I tried to imagine boys dressed in linen clothes studiously reading their assignments and girls with braided hair scribbling letters of the alphabet. I wondered, did many kids attended school in the old-west or did they spent their days working the frontier farms? Was school just for boys, or did the girls have equal access to education?

I walked to the front of the classroom where a teacher’s desk commanded attention; a brass bell – an instrument of superior and undisputed power – rested upon it. So many little lives were managed and directed by the ring of the brass bell. Today, all its power is gone and so are the people who with eagerness or apprehension responded to its dings.

I looked up and met a solemn gaze of George Washington looking at me from his portrait above the desk. “Back in 1776 I could not imagine this kind of America,” he seemed to say. His gaze was intercepted by President Lincoln dutifully guarding the classroom from the adjacent wall. Lincoln had a different message, “kids, you are far out here in the western prairies but there is only one America, and the state of the Union is strong.” By 1884, President Lincoln was already assassinated, and the Reconstruction period was followed by an era of Redemption – but the wild-west had a unique set of problems.

I am amazed at how little an average American — if I may call myself such — knows about life in the wild-west. The gap in our history education is filled by Hollywood motion-pictures and the director’s cuts. I only studied U.S. History as a junior in high school when I learned about the Pilgrims, George Washington, Louisiana Purchase and the Civil War. I did not learn anything about the frontier-life. Americans who travel to Europe marvel on how much history Europe has and lament on how little we have in the United States. Perhaps this is not a matter of America not having enough history but rather a matter of Americans not being suitably exposed to all the history that we do have.

As the sun was setting on Cody, my father and I got into our car and drove back towards the East Entrance to Yellowstone. As we drove through colorful rock formations and picturesque river-bends, I thought, what arguably our country lacks in history, we more than make up for with the natural wonders of our land.

Beautifully written, Irena. I was transported to another time and place over my Cheerios this morning !! Thank you.

Thank you, this one took me almost a week to write and many re-writes. Erik was my editor.