I’ve been purified, released from my earthy, misguided ways. I have climbed the sacred Fujiyama and therefore I am cleansed. I can now enter the heavens, but not too soon. I prefer to wander the Earth just for a little while longer. The place and its people amaze me.

On Monday, June 26th after traveling on the Osaka Metro, Hikari Shikansen, Fujikyu bus, and a local train, I arrived at the Mt. Fuji Hostel Michael’s in Fujiyoshida. At the entry to the establishment, I took my shoes off and checked into a private Japanese-style room. Inside, I gently stepped onto a soft bamboo floor and looked around. By the wall to my right, laid meticulously folded bedding with a sign above explaining in English how to setup sleeping arrangements using the traditional Japanese futon. In the center of the room, sitting low to the ground, was a cheap plastic coffee table threatening the visitors with its flimsy construction – the hard creamy-yellow plastic could crack at any time. I looked once around and then twice, but I did not see a single chair in the room. No chairs – no bother, I am a low to the ground person and sitting on the floor is my modus operandi.

What a luxury to have my own private room, I thought; especially since next to me was a bunk room with five double-decker bunks, a total of ten sleeping spaces. I would do all right in there, too – but I appreciated the luxury and the privacy provided by literarily paper-thin walls.

After getting situated in the room, I stepped out to the public lobby and met Michael, the owner of the hostel. Michael was an ex-US military from New York, who married a Japanese woman and has lived in Japan for over thirty years. He seemed totally assimilated and happy but certainly enjoyed engaging in an English language conversation.

Michael double-blinked his blue eyes and engaged me, “What are your plans while in Fujiyoshida?” he asked, shuffling papers on the front desk counter.

“Tomorrow, I will climb Mt Fuji,” I responded with excitement and conviction warranted of crossing an item of my list of life’s desires.

“Ah, Mount Fuji. We are off-season now and all the huts are still closed.” He provided this information as if I wasn’t aware of my off-season travel schedule.

“The weather has been bad lately and there is lots of rain in the forecast … and a possibility of thunderstorms. It might not be safe to be on the mountain tomorrow,” said Michael, displaying a genuine concern for my well-being.

“I will not be climbing alone. I hired a local guide,” I replied, then added, “for safety.”

Michael looked directly at me, his blue eyes expressing a concern that hadn’t evaporated with my assurances.

I sensed that he felt obligated to enlighten me by providing sage advice. “Guides – People hire guides, but they are no good. They are in it for the money. Many are not even locals, they come from Tokyo to lead people.” Michael paused, adjusted two stacks of papers then continued. “If it thunders on the mountain, drop down close to the ground. It is bare up there and you will be the highest point. Thunder strikes the highest point, so drop down low.”

Michael continued after taking a short breath, “People die on the mountain, maybe ten per year or so. Locals don’t like to go up there, Fuji is a god and god should be respected. Fuji is a sacred mountain. My wife went up there once, many years ago. Here is here walking stick.” Michael pointed to a staff hanging above the reception. The shiny brown branch of wood, adored with beads, was smooth, graceful and a little wavy, very aesthetically pleasing.

I felt a need to assure Michael of my capabilities to make good decisions. “If the weather is bad, I do not need to reach the peak. I am OK going up a little way then coming back down. Making an attempt is good enough for me and I certainly have no intention to endanger myself.” I did not want to say anything else about my confidence in the local guide, because Michael did not give much credence to that concept.

“Well, if anything happens no helicopter goes up past the eight station. Good luck to you.” He adjusted colorful travel brochures then looked up at me again, “There was a guy who went up a couple days ago and he said that most of the snow melted. Huts are still closed but some bathrooms might be open. Oh, and the bulldozers are working on the access roads.”

While he was talking there was a lot of commotion coming from the ten-bunk bedroom. Michael looked in the general directions, “Those are my usual guests. A few Japanese guys. They are nice and will settle down during quiet hours. No need to worry about the noise.”

I wanted to appear easy-going, so I responded with, “No worries, I am heading out to grab some food.” I intended to make this an early evening since my wake-up time was 4:15 AM for a 4:45 AM pick up and departure to Mt. Fuji. I recently read a book about an expedition to Mt. Everest, Into Thin Air. Numerous people from the expedition died on the mountain and with Michael’s warnings and the fresh memories of the book, I had a restless night. My alarm went off at 4:15 AM, but I gave myself an extra five minutes of slumber, then I got my stuff together, signed out of the hostel, put my shoes on by the front door, and went outside to meet Chika, my local guide.

Chika, promptly waiting for me in the parking lot, was standing by her Toyota hybrid minivan. We greeted each other and I proceeded to the front passenger seat. Chika gave me an awkward look and giggled. I realized that I was going to the wrong side of the car, I was not the driver, and Japan’s traffic follows British rules, cars drive on the left. I laughed and walked over to the left side of the car where a passenger should sit.

Our first stop was for provisions at a local 7-Eleven, a convenience store very much like what we are familiar with in the United States. I carefully selected a couple sandwiches, but when I noticed Chica by an upright cooler grabbing rice patties, I put down my western-style sandwiches and walked over to that cooler. I carefully chose two rice onigiri; one had a Japanese egg omelet on the top and the other a slab of salmon. While in Japan do as the Japanese do.

Our destination was the 5th station of the Fujinomiya trail located approximately 2400 meters above sea level. This trail had the shortest ascent of about 4.3 kilometers but was also the steepest. Chika parked the car and we began to inventory our climbing equipment. I had a 40-liter backpack which contained my overnight traveling items and also a 12-liter mountain biking hydration backpack. I could take either one up the mountain but preferred to go with the smaller pack. Chika looked at my well-organized, efficient packing arrangement and approved of the smaller pack. She handed me a helmet and said that we shall put the helmets on at the 9th station and wear them all the way down.

Standing by the open back gate of Chika’s minivan, I felt anxious about climbing Fujiyama – many people view the trip as a sacred journey, Fuji-san is sacred; it is a god. I wasn’t sure what level of difficulty I signed myself up for and I felt like an expecting mother before birthing my first child. Chika would be an obstetrician guiding me through the birthing process, but until it was all over, the just-about-to-happen experience felt intimidating.

There was mist in the air and we put on our rain gear. Mine was a twenty-six-dollar amazon-supplied forest-green set that included cheap plastic rain pants and a matching rain jacket, both a little too big for my body frame. The air around us was sticky and while serving as an external barrier, the cheap water-proofed attire did not expel my internal moisture. I really didn’t like wearing it but I also did not want to get soaked by the rain. My options were either to get drenched by the rain or by my own sweat.

We stepped up to the informational board with a map depicting our geographical journey. The rain was easing so I happily took off my rain pants and rolled them into a tight sushi-like roll then shoved them into my pack. My lower body could breathe freely again – luxury. Comfortable, I was ready to look at the map and analyze topographical details. Mount Fuji has four approaches: Yoshida trail, Subashiri trail, Gotemba trail, and Fujinomiya trail. The lattermost was our trail for the day.

From the altitude of 2400 meters, we started climbing on the wet, rusty-brown volcanic soil, carefully stepping onto large rocks that littered the hiking trail market by two laid ropes. The first stop was at the 6th Station located 2,490 meters above sea level. Mt Fuji summit was still 3.8 kilometers away and the odds for the ultimate achievement were not yet clear, but the 7th Station was only 1 kilometer away, a distance not too intimidating to embark upon.

At the 6th station, we took off the rest of our rain gear. I was happy to peel off the cheap plastic jacket figuring that I’d rather be wet from the natural mist than moistened by my own sweat.

It was time to move — up and up the Fujinomiya trail we went. The trail where Mount Fuji, the god, managed to balance the world by pairing the short distance with sharp and slippery obstructions of infinite volcanic rocks, sometimes too high to step upon. This was a spiritual journey and I was in the zone doing the spiritual thing that I am normally not accustomed to partake in. As we climbed, I took numerous opportunities to stop and in a non-spiritual way take selfies and panoramic videos of the magnificent landscape reminiscent of a Martian surface.

7th Station, altitude 3,010 meters. Mount Fuji Summit is only 2.1 kilometers away, and only 570 meters to the 8th station. The time was ripe for the first snack of the day. From the translucent plastic wrap, I unfolded my 7-Eleven rice patty, the one topped with tamagoyaki, the Japanese egg omelet. I wasn’t thirsty but aware of the steep ascent and worried about altitude sickness, I took a couple small gulps of water. This was a short rest but we had mountains to climb and spirits to visit.

Chika commented that we were lucky to do this trip off-season because during the season, Mt Fuji gets extremely crowded with tourists. The trails get uber congested making it impossible to walk at one’s preferred rhythm. During peak times, it is the stride of the slowest person somewhere in the long chain of humanity that everyone is paced by.

After the 7th station, big rocks gave way to smaller rocks that looked like rusty-red Martian baby skulls covering the southern slope. Chika smiled as we reached the 8th Station, altitude 3,250 meters. Mount Fuji summit was only 1.5 kilometers away and the 9th Station was just 570 meters up from where we were. The weather was holding up well and the odds of achieving our goal were turning in our favor. At this altitude the mist was gone; it was as perfect as perfect could be.

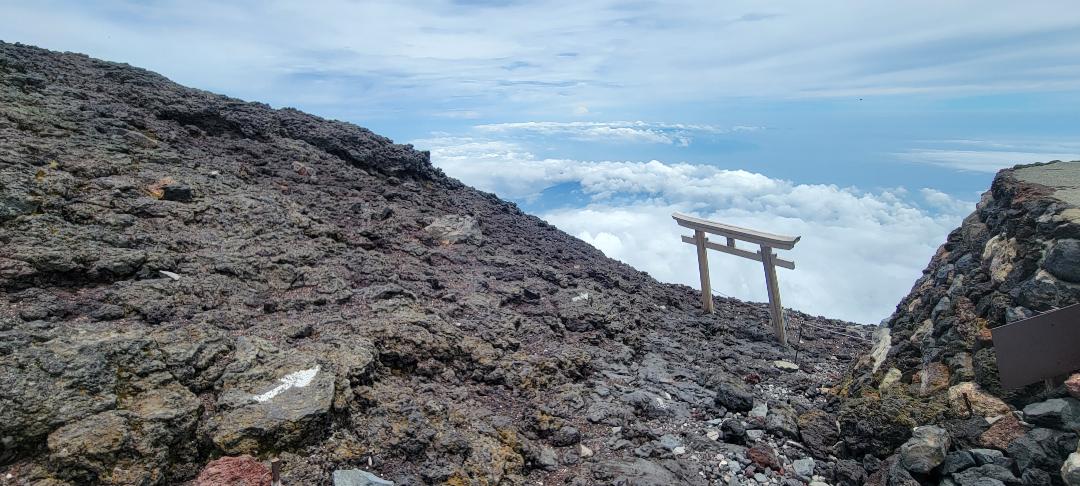

In the distance, above the 8th Station protruded two round wooden poles bisected by two horizontal bars, a Shrine, marking the entry into the sacred land. The top bar had a slight up-arc towards the sky. I closed my eyes trying to force a spiritual awareness, but spiritualism cannot be forced.

A little way up on each side of the path rested two poles but without the bisecting horizontal bars. Each vertical pole had metal coins inserted into the golden, petrified wood creating an artsy decoration. These were remains of an older shrine and the coins were five-yen discs with a hole in the middle. Apparently, the Japanese pronunciation for “five yen” is identical to “go-en,” which means “good luck.” Too bad that I did not know that at the time and therefore didn’t leave my good-luck mark in the shrine’s post. Just behind the post on a gray rock, there was a painted white arrow pointing to the summit. Chika and I kept walking.

The scenery changed again, this time we could see a few remaining patches of snow. Our next stop, the 9th Station at an altitude of 3,460 meters. From here only one kilometer remained to the summit and Station 9.5 was just 440 meters away.

Really, Station 9.5?

Did we just enter into a scene from Harry Potter?

Or maybe this is a lesson in calculus – as the limit approaches the Fujiyama summit, the remaining distance is split in half, and then again and again, meaning that we will never actually reach the summit.

Is this what spirituality is about?

We took a short break and since all the facilities were still closed, Chica got a disposable toilet, aka a fancy zip-lock bag, and went behind the building to perform her business. I was pleased that my physiological nature was not requesting a relief because I was afraid that while peeing into a zip-lock bag, I might pee all over my hands and who knows what else. But not needing to pee this far into the journey, could imply dehydration and that would not be good at this altitude. I pulled out my bottle of water and took a few healthy gulps. Altitude sickness is nothing to mess with and a significant number of climbers do experience it, in most cases in its mild non-dangerous form recognized by feeling lightheaded and dizzy. Other symptoms include increased heart rate and trouble breathing when active.

Wait – I was experiencing all of this.

Then comes nausea and fatigue, symptoms often described as similar to a hangover.

Fortunately, I am an experienced hanger-overer and walking while drunk is my superhero power. Maybe the steepness of the slope and the high steps of sharp volcanic rocks could propose a certain additional challenge, but I like challenges and after all – this was a spiritual journey and having an out-of-body experience could be a meaningful part of it.

As I rationalized my mild altitude sickness symptoms, Chika came back from behind the building carrying a small baggie of her liberated internal liquids. To follow the proper etiquette, she packed the baggie into her backpack to carry the waste out of the sanctuary.

Then Chica looked in my direction and asked, “Are you ready to climb to station 9.5?”

There really is station 9.5, the altitude sickness is not messing with my ability to read signs.

“Yes, I am,” I eagerly responded. “Let’s do it,” we put our packs on and slowly proceeded up the mountain.

Station 9.5, altitude 3,590 meters. 550 meters to Mt. Fuji Summit and 550 meters to Sengentaishi-Okumiya Shine. The weather was holding up, we were experiencing perfect conditions for this adventure. At the higher altitude, it was cooler so Chika and I put on light jackets that made us feel warm and comfortable. As previously advertised, Chika instructed me to put on my helmet, an orange hard hat that made me look like a construction-worker.

I had a strong desire to object, but before I was able to utter a word, Chika put a helmet on her own head and said, “Fuji is an active volcano and once in a while there might be rocks coming out. It’s a small chance but when it happens it could be tragic.”

I no longer felt like objecting and put the orange bucket onto my head thinking, At least I will have some cool pictures to post. Wearing a helmet depicts this as a real, dangerous adventure.

We looked up into the blue sky and started to walk onwards. Closer to the summit there was a lot of work going on. Just as Michael told me in the hostel, there were yellow bulldozers working on clearing access roads. In the season, these roads are used to bring supplies to the huts and the season was about to begin in one week.

The final approach was very steep and full of slippery gravel. I took a step up and then my foot slid seventy-five percent of the way down. To the side of the path there was a solid fence. We held on to the posts of the fence as we made our way upwards. It was slow going but we were so close to the summit that nothing could stop us now. To our right was the vastness of the Fuji-san crater, looking like a steep valley. I imagined the crater of Fujiyama to be a deep hole reaching down to the center of the Earth, but this was a valley with a rocky floor.

Managing the slippery slope, Chica said, “In the winter when the snow covers the peak, people come here and ski into the crater.”

“Really?” I was genuinely surprised. “How do they get out?”

“They climb out,” Chika said, probably surprised by the stupidity of my question.

“I guess, there is not a ski lift on Mt Fuji.” I kept digging the hole of stupidity.

“Nope, no lift on Fuji.” Chika confirmed my astute observation.

We arrived at the summit where there were two other groups of pilgrims. A few feet away to my right sat two middle-aged Japanese women eating lunch and chatting energetically. To my left, a family of three people was taking pictures at the obelisk that signified the tippy-top of Mt Fuji.

I once again felt fortunate to do this climb off-season, no crowds, no lines, and each of us could pose at the obelisk as long as we wished to immortalize our journey.

Chika and I sat down by the weather station building. For many years, meteorologists stayed at the station to monitor the elements but with the advent of modern technology commitment to solitude is no longer necessary.

From her pack, Chika pulled out a thermos with hot water. “Would you like coffee, tea, or hot chocolate,” she asked.

I was not expecting such a luxury at the summit of Mt Fuji. I figured that green tea might be the most appropriate Japanese way to celebrate a successful ascent. Chika put dry tea into my cup and poured hot water over it. As my hands hugged the plastic cup full of steamy liquid, I looked around with satisfaction. Five hundred dollars for a private guide to climb Mt Fuji off-season is not cheap, but as I sat on a very uncomfortable volcanic rock, I felt like the experience was worth every yen.

Chika appeared lost in her own thoughts. As a guide, she does this climb a number of times per year, I wondered if each time it is a spiritual journey for her. I didn’t want to ask.

“Are you ready to go and see the shrine?” Chika broke our silence.

“Of course, but I would really like to walk around the crater. I guess that probably would take too long,” I replied with a little hope that Chika would grab onto my idea.

“It would take a few hours and currently the path around the crater is closed. It will reopen in the season. Let’s go visit the shrine.”

We got up and gathered our stuff, packing everything including trash to take off the mountain.

The shrine was a short walk away by the edge of the crater. Water from melting snow flowed in narrow streams, cutting through our ashen path. I didn’t want my shoes to get wet so like a frogger I hopped over the streams.

At the shrine, Chika performed a Shinto ritual, she held her hands in a prayer position, bowed twice, clapped twice, and bowed again. I watched with interest, wishing that I could video this simple ritual and post it on the social media but that, I felt, would be an invasion of the sanctity of this place and an infringement on Chika’s relation with it. Something that I definitely did not want to do.

Chika decided that as opposed to going down the way we came, we could use the access roads. That might not be OK to do during the season but off-season it did not seem like a bad idea. Unlike the official hiking trail, access roads did not have the large volcanic stepping stones but were covered with a fine volcanic ash. Our feet were sinking deep into the ash. Each step was a long-controlled slide. We were skating down, not walking. After a few meters, we got used to the sensation of sliding. Then all of a sudden, woosh and Chika landed on her backside. I prayed that she was all right because if she happened to twist her ankle, it would be a beast to evacuate her down. Luckily, she was all right and we proceeded down the well-defined zigzagged access road. Then woosh, I lost my balance and this time it was me landing on my butt. Plopping down into volcanic ash I felt fine powder getting into every available fold in my clothes and every exposed crevice of my body. By now my shoes were full of it and I had a lot of ash in my socks. While sitting down, I took the opportunity to take off my shoes and socks and shake out the rusty soil. Chika watched my performance and when she realized that I was all right, she pulled out her canteen of water and took a few sips. We were making good time down the face of Mt Fuji. Soon we got to the 6th Station where we joined the regular hiking path. In my opinion, slip-sliding down the access road was a bigger challenge than climbing up the proper hiking path. Every muscle in both my thighs was screaming.

At the end, we made the journey in under six hours. Our moving time was 4 hours and 48 minutes. A record time for me, entirely due to the fact that it was and remains my only recorded time on Mt Fuji. We traveled a distance of 7.91 miles and gained 5,231 feet in altitude.

I came to the sacred Fujiyama hoping to be engulfed in a spiritual experience. The slopes of this majestic volcano are home to Shinto Shrines and offer a spectacular place for prayer and reflection. While I was washed by the heavenly mist and bathed in the glow of golden sun rays, for me this was simply a hike. I cannot credibly say that: I’ve been purified, released from my earthy-misguided ways. I have climbed the sacred Fujiyama and therefore I am cleansed. I can now enter the heavens, but not too soon. But I can say that I prefer to wander the Earth just for a little while longer. The place and its people amaze me.

Note: Special thanks to my newest editor and a fellow Mount Fuji climber, Asher Tlalka Scott.

Mount Fuji Crater

I loved that story! Very informative and entertaining. Makes me want to go now!